For years, Wild Heart Wildlife Foundation has been working to raise the awareness about the merciless slaughter of these Vanishing Giants, strengthening their protection, and caring for the survivors. Has it all been in vain? It certainly seems like it's over for the Rhinos in the Kruger National Park.

We are customizing an expensive hydraulic operating table for rescued Rhino Babies and you can help! Make a difference by supporting our 8th Annual Xmas Fundraiser for The Rhino Orphanage here:

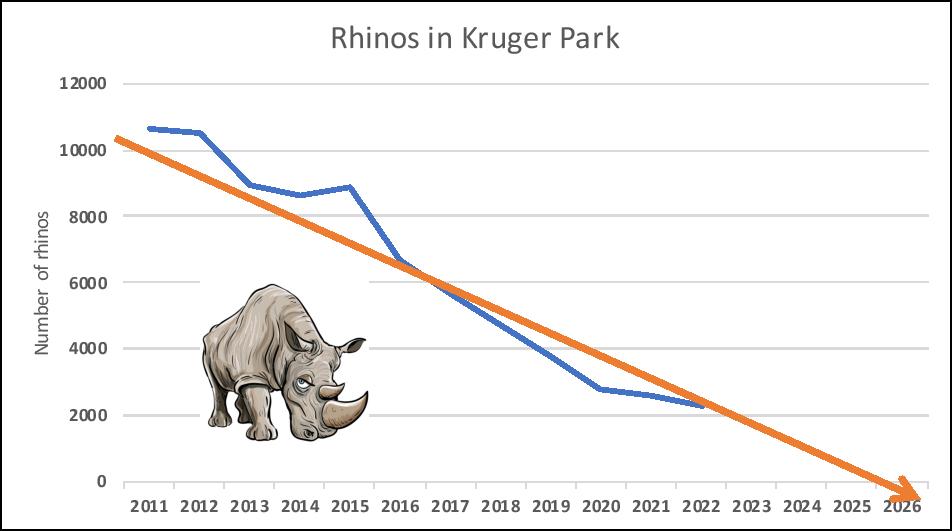

Kruger National Park, the world’s greatest refuge for rhinos, is losing them to poaching faster than they’re being born. The park’s last Rhino may already be alive. It’s time to declare an emergency.

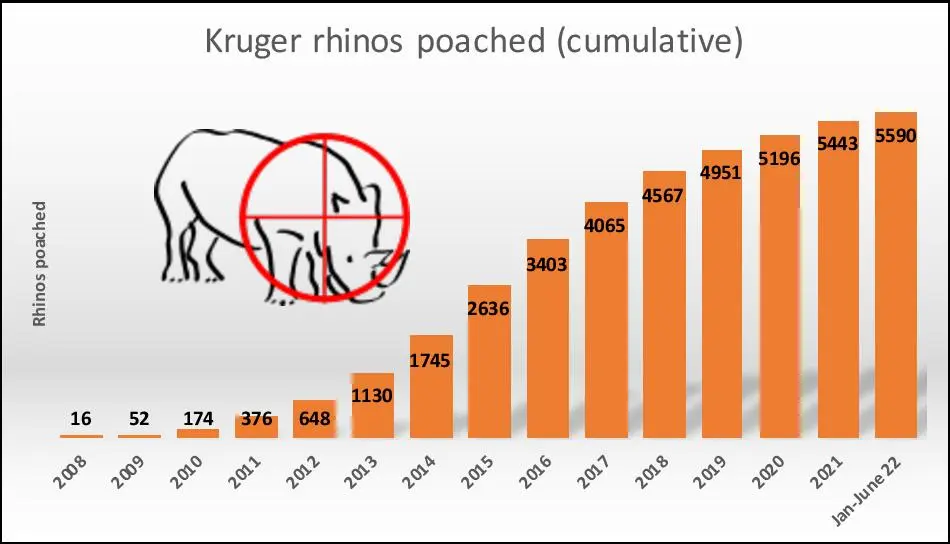

Under the heading Progress, the 2022 SANParks Annual Report has a deeply disturbing and immensely sad target claimed as a success: only 195 rhinos were killed by poachers during 2021 – an average of one every two days. The success, it seems, is that the previous year it was one rhino every 36 hours.

In its reports and pronouncements, SANParks acknowledges poaching problems, but the overall tone is “don’t panic, we’ve got it under control”. They haven’t. Kruger is bleeding rhinos and is in need of sutures – fast.

The Department of Forestry, Fisheries and Environment (DFFE) has disclosed that in the first six months of this year, 82 rhinos were killed in the park. If the trend continues, the year will end up with a kill rate equal to 2021.

The truth is that unless Kruger does something fast, Rhinos could go extinct in the park within four years. That’s far shorter than the lifespan of most rhinos in Kruger.

Since 2009 – just 13 years – rhino numbers have dropped from 11,420 to 2,458 and this year they will continue to drop. During that time, the number of rhinos poached was double the existing population.

The cumulative numbers are shocking. There’s a good chance that Kruger rhinos are on the way to becoming functionally extinct, as these graphs clearly show.

Where do the problems lie?

What will it take to bend the curve upwards away from zero? The answer can only come from understanding the reasons for the decline.

SANParks will point to forces beyond their control – and they are considerable.

Like a snake eating its own tail, the problem begins and ends with a seemingly insatiable appetite in Asia for rhino horn, which is seen as both a status symbol and cure for various ailments (it isn’t).

This has led to a situation where highly organised international crime syndicates supply weapons and logistics to local middlemen who induce impoverished young men in communities on both sides of the park to poach rhinos.

The park is sandwiched between millions of mostly poor people – Mozambican and South African – with few prospects for employment. It’s fertile ground for poacher recruitment.

Kruger Park also has unfenced borders with a parallel park in Mozambique, but rangers following poachers cannot cross the line.

In his book, Rhino War, written with Tony Park, General Johan Jooste – who was Kruger’s head ranger from 2013 to 2016 – was told by a ranger: “They laughed at us, General. As soon as they crossed the border they stopped and started waving at us, yelling insults. They know we cannot chase after them.”

These issues alone, however, cannot be the sole reason for the precipitous decline of rhinos. There are serious internal problems as well, mostly, says Jooste, to do with ability, capacity, integrity and vision.

Buffet’s cancellation

A retired military officer, Jooste was brought in as head ranger in 2013 as rhino poaching began escalating. Donations formed the backbone of his development strategy and with them he created a highly trained paramilitary force out of the ranger corps. He also brought in high-tech surveillance equipment.

Jooste negotiated a R225-million anti-poaching grant from billionaire Howard Buffett, using it to create an efficient joint command centre to gather and coordinate intelligence against poachers.

Then, in 2016, Buffett cancelled more than half of the grant, citing the absence of a reporting structure with clearly defined roles and lack of internal capacity for project management. Millions were wasted on internal inquiries into this loss.

The collapse of Intensive Protection Zones for rhinos – set up by Jooste during his tenure and funded by Buffett – started coming apart after his departure. They did so, he says, because Kruger and ranger leadership failed “to carry them through and find a way to make them work or come up with workable alternatives”.

It was an “abdication of duty and lack of courage”.

Buffett’s bequest had been received with great fanfare, but evidently not universally within SANParks’ executive ranks.

Buffett’s generosity was based on his personal regard for Jooste and, according to the book, Rhino War, this rankled with those who didn’t appreciate being beholden to a rich American who had made it clear that his largesse would only be in place as long as Jooste – the white ex-apartheid general – remained at the helm.

Integrity testing

Jooste resigned under circumstances he is not willing to discuss; details of which are largely absent from his book. He alludes to “problems”. The park clearly not only lost necessary funding, but a key strategist in the rhino war. One of the problems, it seems, was integrity testing.

“Members of Exco feel you’re acting outside your mandate in pursuit of corruption after integrity testing,” he was told. Integrity testing was the euphemism for the polygraph testing of Kruger staff. From the outset, Jooste had insisted on this intervention and was the first to subject himself to the process.

Integrity testing was not popular, but Jooste felt it was necessary.

Poachers were paying some rangers to locate rhinos and a few were even involved in actual poaching. These included Rodney Landela, who Jooste had promoted to regional ranger.

Unions were also opposed to polygraph testing and it was suspended during the Covid pandemic. SANParks has undertaken to renew it, but has as yet failed to do so. It is not known whether a proposal for integrity testing was finally submitted to the SANParks board in November.

In his book, Jooste says testing without steps being taken on the results is useless. While Kruger management knows that leaks on rhino locations are coming from staff, they seem to be dragging their heels on making integrity testing happen.

Ranger shortage

Kruger also has a ranger shortage. More than 80 posts were not filled this year despite a commitment to do so obtained by DA shadow minister David Bryant.

They had not been filled for several years. SANParks explained the problem as a budget issue, despite millions being spent of anti-poaching initiatives.

It is unclear and counterintuitive that these posts are not budgeted for and filled as a fundamental step in the poaching war.

Strongholds

Beyond Kruger Park, rhino conservation is another story and is in an intensive planning stage. Although the park has the largest single population of black and white rhinos, around 60% of the national species are in private hands and many others are in national and provincial parks other than Kruger.

According to SANParks’ Annual Report, strongholds beyond Kruger are being constructed, though it doesn’t say how advanced this is or quite how this programme will work. It’s clearly not in the interests of rhino safety to say where they are or will be.

There will be pushback from conservationists. They point out that placing rhinos in private hands has led to the crisis of rhino farming for their horns, which keep “leaking” on to the black market. This fuels both Asian demand and poaching. There’s a fine line between conservation and commercialisation.

In Rhino War, Jooste writes of Kruger: “A decade into the rhino campaign, my overwhelming realisation is that we cannot afford another 10 years like this, even with our successes. We must avoid another ‘runaway train’ situation at all costs.”

If the statistics are anything to go by, that train without brakes has already left the Kruger Park station. DM/OBP

Republished with permission from Daily Maverick.